Being a physician today bears little resemblance to the profession in Dr O’Gormans grandfather’s time, whose generation worked out of their home and made house calls.

_____

It was in Monaghan, Ireland that Dr O’Gorman and his ancestors began their love of medicine.

There is something wildly mystical about spending time in this region of Ireland, devoid of crowds and hustle; when getting lost and enjoying the company of others is the plan. Dotted across the county are towns so pretty amidst rolling drumlin hills that it’s a wonder that anyone would ever want to leave.

We sat down with Dr O’Gorman to uncover where his love of medicine started, and what he thinks his own legacy might be.

You’re someone who has long championed and highlighted the incredible work of your grandfather. How different was medicine back then?

O’GORMAN: Rewind almost 90 years and my grandfather had just finished medicine at University College Dublin. It was 1932. Ireland was a country on its knees, crippled with unemployment at a time when the world was in the grip of the Great Depression. Farmers were forced to endure very low prices for their crops and agricultural labourers were earning as little as 15 shillings a week – barely enough to survive, much less to feed a growing family.

My grandfather practised from his home in Monaghan. GP care was not provided for by the government at that time. He did his best to judge who might be able to pay and others who he would insist on providing care without cost. And indeed a barter system was alive and well with patient’s bringing eggs, mushrooms, potatoes etc. Care then was complete within the consultation. He had his own little lab behind his consultation room where he would view his patient’s blood under a microscope. He cared for his patients from birth to death, delivering babies, and performing autopsies after death.

“He did his best to judge who might be able to pay and others who he would insist on providing care without cost.”

Back then many houses were still without electricity or running water. Health was poor and infectious diseases were common. I cannot imagine the challenges he would have faced.

_____

How did he find a balance between hard work and family?

O’GORMAN: My grandfather had many hobbies outside of medicine. He was also a great carpenter and mechanic with a love of vintage cars. He once drove his vintage car all the way from Ireland to Turkey where he won the vintage rally. He also had a love of cycling and rode extensively to raise funds for research into Multiple Sclerosis (MS). When he lost his sight in his 80’s, he and my Dad took to tandem cycling (neither ever said no to a challenge)!

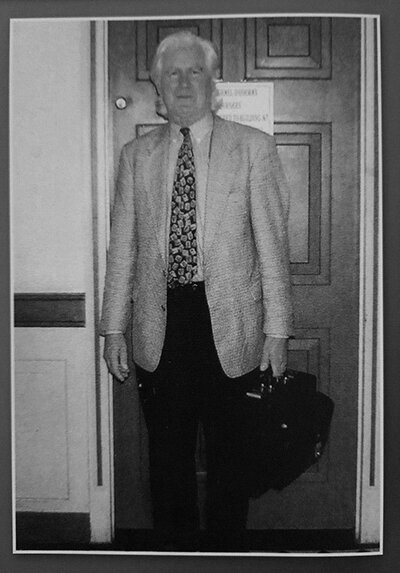

I am so privileged to have his leather doctor’s bag and Welch Allyn diagnostic kit which he kindly gave me when I started medical school.

_____

Who else in the family practised medicine during this time?

O’GORMAN: My other grandfather, my mother’s father, Dr Conn Ward, was also a GP in Monaghan. He also practised from his home, as was the norm at that time.

Grandfather Ward fought in the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War and then went into politics to become the equivalent of Minister for Health in Eamon de Valera’s government. He was instrumental in introducing the maternal and child health scheme in Ireland, as well as opening many hospitals during his time.

I have the presentation keys that were presented to him at the opening of these hospitals hanging in my study.

_____

And your father followed in your grandfather’s footsteps?

O’GORMAN: Yes, my father shared not only my grandfather’s passion for medicine but his passion for cars, carpentry, and cycling! He differed in pursuing competitive sailing and hand gliding, however.

Dad qualified from University College Dublin in 1962. After a number of years in hospital medicine and surgery, including a few years in Scotland, just like his father he started as a GP in Co. Monaghan and initially he had his practice in our home.

Growing up, I spent a lot of time travelling with my Dad on his home visits. My role was to open and close the many gates that led up to each farmhouse, and sometimes accompany him into each home where tea and biscuits were always on offer.

I am privileged to have my Dad’s watch which was presented to him by his parents at his graduation.

_____

How did your father inspire your love of medicine?

I spent a lot of time working in his office on weekends or during school holidays. As I shadowed him, I got to see the love that he had for his work and patients, and how grateful his patients were to see him. Like his father, he was shy to accept remuneration and his patient’s made up for it with food and drink. There were many memorable moments including the unexpected delivery of babies in his office, and I remember an enquiry came in asking for him to remove a bullet from a terrorist’s body! Our town straddled the border and terrorism was rife at that time.

I observed and absorbed a lot. It was never suggested to me that I might study medicine, but by the age of 14 or so, I knew medicine was to be my path.

_____

Do you think your upbringing also had a major part to play?

Growing up in Monaghan was a great experience. We were a family of eight children. It was common to have a large family and eight or nine children was not considered to be too big in those days!

We spent our days outdoors; cycling, playing in the hay during the summer and in the snow during the winter, often not returning home until tea time. As children, we were far less supervised and entertained than kids are these days.

Our parents set up a local swimming club and we all swam competitively. I remember a bulldozer appeared at our house one day and started digging and the next thing we had a swimming pool in our garden. I can’t say I relished an outdoor pool in Ireland!

“I remember a bulldozer appeared at our house one day and started digging and the next thing we had a swimming pool in our garden.”

I loved cycling, as it gave me a great freedom and I have fond memories of cycling the Round the County 70km charity ride with my dad and grandfather. I recall struggling to repair my bike and wanting to give up but my Dad insisted I refocus saying there is no such thing as can’t – I recall this often and that lesson helps me to this day.

We did a lot of things together as a family and I know this gave me a real insight into medicine long before I started thinking about a career path.

_____

How did your career in medicine begin?

When I left University College Dublin it was 1992. After a few years in hospital medicine, I also specialised as a GP, which was an excellent grounding into general medicine and experience with developing close patient relationships.

I arrived in Australia in 1997 on a working holiday, and of course, I am still here!

Whilst practising in Melbourne, I realised that I particularly enjoyed hands-on work such as excisions, suturing, applying plaster of paris etc. This led me to explore the world of cosmetic medicine.

Aesthetic medicine is a fascinating mix of science and artistry. I found it such a fulfilling area of medicine to practice as it allowed me to utilise my visual brain in a personal way for my patients, and to be involved in a dynamic and constantly changing specialty. I never really delved into carpentry nor mechanics like my dad and grandfather, but sometimes I wonder if the genes for carpentry and mechanics assist as I work with precision in the aesthetic field…

I have been practising cosmetic medicine for the past 17 years and have not looked back.

_____

What do you hope your legacy will be?

I do think about what I would like to pass on to the future generation of doctors. I think about all the advances that have taken place in medicine yet to me, the single most important and effective tool for a clinician remains the consultation. I believe that the ‘secret is in the consultation’.

When I was studying for the Royal College of GP’s exam, I studied the art of consultation. I was fascinated to learn that the consultation process can be utilised as a therapeutic tool. I also learned the art of ‘active listening’. And I realised that all these years, this was exactly what my dad and grandfather had perfected. They were some of the most astute practitioners of using the consultation as a therapeutic tool. Once the patient entered the consultation room, it became a sacrosanct place. It was not to be disturbed. And the time taken to complete the consultation was without predetermined time, regardless of the appointment schedule. And patient’s did emerge much lighter and left with obvious content. My dad and my grandfather practised active listening with their patients, as I do today.

“I believe that the ‘secret is in the consultation.”

I also utilise consultation in cosmetic medicine in the same way. As I perform the treatment, this is my opportunity to really get to know the patient, how their lives are going, what makes them tick, what challenges they are facing, gently prying, actively listening and supporting them.

It is one thing to assist in improving skin and appearance concerns, but adding in the whole person gives a much more fulfilling and satisfying experience to both the patient and the doctor.

My advice to the future generation of doctors is to study the art of consultation, to use it as a therapeutic tool, and to practice active listening. This will differentiate doctors who excel from doctor’s who have a more mediocre career experience.

I am just as passionate about medicine today as I was on qualifying in 1992!